I Don’t Know Why I Love You, But I Do

Being the True Confessions of Matt “D’Israeli” Brooker

I Don’t Know Why I Love You, But I Do Being the True Confessions of Matt “D’Israeli” Brooker |

|

|

I suppose it all started at Ed Pinsent’s panel on creativity at Caption96

[an annual small-press convention in Oxford, UK—ed.] during a discussion on the effect of the quality of work on creative block (i.e., if you feel your work is bad you’ll be more prone to “block up”), I asked whether anyone else ever found their own work to be more likeable than good. Ed, rather sensibly wanting to avoid the whole business of defining quality, rapidly steered the conversation elsewhere and that, so I thought was that. But then a few weeks ago Fiona Clements [one half of the current Contents editorial team—ed.] rang me to ask if I’d like to write an article explaining what I meant in more detail, and now the deadline is approaching...I’ve never had any trouble admitting that I like comics which are no good. There are also comics which I know to be good, which I don’t enjoy. If we’re to explore this, first of all, we have to set our definitions: words such as “Good” or “Quality” are notoriously difficult to define. In the examples given here, I’ve tried to pick works which are: a) well crafted; and b) generally considered to be worthwhile. I hope that that way, if you disagree with any of my choices, you can at least see that there is an argument for placing them in that category.

So, how to proceed? I’ll first give two examples, one of a “good” comic I don’t like, and one of a “bad” comic that I do. I’ll then show the factors that contribute to Charm (or the lack of it), and finish by seeing if I can apply these to my examples to explain my reactions to them.

Take the Hernandez Brothers’ Love and Rockets—if you were asking me to recommend ten of the world’s best comics, then this would be near the top. I’ve read numerous favourable reviews of L&R over the years, and have to agree with all of them—but unfortunately, when reading it, I only seem to be able to appreciate it as a kind of technical exercise; Fiona Jerome wrote that it “opens up to me worlds of experience that are at once troubling and exciting... it pulls off the trick of emotional authenticity” (Note 1), yet for me it remains opaque—like the joke you just don’t get.

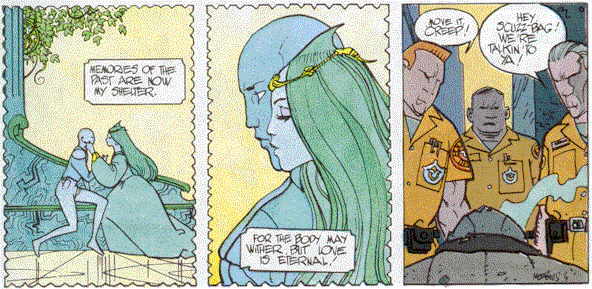

Illo #1: by Jaime Hernandez

From Love and Rockets 15

If Love and Rockets is loved by one and all, then the opposite is true of my second example, Moebius and Stan Lee’s Silver Surfer (Note 2). Here is a truly despicable comic—Moebius fans found the very concept an embarrassment, the Surfer fans hated its poncy, over-hyped artwork. It was ponderous and pretentious, and never available in a decent edition—you had to choose between the ultra-cheapo newsprint version where half the linework didn’t print or the obscenely expensive hardback edition where the colours became offensively intense because they printed it on glossy paper. Who could possibly love such a cynical attempt to exploit two readerships similtaneously?

Ahem.

Illo #2: by Stan Lee and Moebius

Ahem, indeed

The element I’m trying to isolate is one that you could call “Charm”. It’s the quality which makes you really like a comic regardless of whether you think it’s any good or not. This isn’t to say that good comics can’t be charming too—in fact I must point out that the comics I use as examples aren’t being singled out or assumed to be “bad”. I’ve just used what I hope will be the most widely known examples (given my own conservative reading list) for each ease.

1: Nostalgia

Most of us have at least one “special comic” which is either part of our fond childhood memories, or associated with that “Road to Damascus” moment when we realised just what a powerful medium this could be.

Years later, on re-reading these treasures, we may well find that they’re not the works of genius we first took them for, but somehow, that old glow never quite leaves them. This effect can also apply to a really good pastiche (see next paragraph).

2: Reader Naivete

When creators “borrow” a concept unfamiliar to their readers from another source, the resulting comic will appear more innovative and original than it actually is. This may be deliberate on the part of the author, or it may be the result of unexpected ignorance on the part of the readership. Example: Watchmen—in creating the character Dr. Manhattan, who experiences every moment of his life simultaneously, Alan Moore adapted concepts invented by Kurt Vonnegut in his novels Slaughterhouse 5 and The Sirens of Titan.

Illo #3: by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons

Dr. Manhattan from Watchmen.(An excellent example of both the previous criteria working in favour of a comic is another Alan Moore series, this time for Image: 1963. Intended as a homage to the original Marvel comics, a large proportion of the readership were attracted by nostalgia—however, a substantial proportion of buyers were young readers, who, ignorant of the pastiche element, treated the whole exercise as an exciting “new” approach to comics!)

3: Concurrence of interest

This sounds rather obvious: the subject matter of a comic has to coincide with the interests of the reader in order for them to enjoy it. This is one of the major factors in the marketing of comics. but the extent to which it influences the reader depends upon the nature of the market. For example, any publisher wishing to launch a new superhero comic faces a market so saturated that the subject matter itself will not automatically guarantee sales—Marvel felt they had to use “Big Name” artists such as Jim Lee on the re-launch of their line in order to attract readers. On the other hand, consider the fad for the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles a few years ago; because of their great popularity, and the fact that the market was a captive one, even uninspired licensed products based on the characters would sell well.

Such crude devices tend to work best with a younger audience, who tend to make judgements using narrower or more simplistic criteria—consider Image Comics, which often subjugate plot and even storytelling to the portrayal of whirlwind action and brutal fight sequences. Though these are considered faults by many comics readers, it is easy to see how they would strike a chord with a readership familiar with current video games. The lesson seems to be that even poor work will sell for a time, regardless of quality, if it follows a popular trend.

4: Shared Experience

Where the theme or contents of a comic reflect the life of the reader, for example Peter Bagge’s humour or Chester Brown’s Playboy stories (if you’re a man!).

Conversely, if you don’t have this experience, this effect can diminish enjoyment of the comic.

5: Idiosyncracy (Good)

The main value of certain works is the novelty of the thought processes of the mind behind them; the work of Dan Clowes and our own Martin Hand spring to mind. In Martin’s work, the pages are filled with a grid of front-on head-shots; drawing is simplified, plot is thin, story sometimes non-existent—dialogue from panel to panel can be non sequitur and occasionally fails to make sense at all. Yet in spite of breaking all the rules, Martin’s work has a deranged brilliance.

Illo #4: by Martin Hand

Idiosyncratic enough for you?

This example also highlights the problems of defining this category, as, like humour, it’s impossible to explain or quantify to someone who doesn’t “get” it.

6: Idiosyncracy (Bad)

This one is easier to quantify—in fact Comics Forum has devoted a number of articles to this sort of comic over the last few issues.

[Our department called “What Where They Thinking?”, which will be appearing here in the next issue —ed.] It is the comic which is “so bad it’s brilliant”—due either to a staggeringly asinine basic premise, inept execution, or often a combination of both. One feature of these comics is that they are often better described than read; I have great fondness for the idea of Neutro, a comic in which the main characters spend all their time discussing what a giant robot might do, if it had a brain.I have never actually read Neutro, and suspect I might be very disappointed if I ever did, but over the years I’ve had hours of fun explaining the concept to my friends. This category is really only good for one thing—humour—even if the creators of the comics never had that in mind. There should be a heroic quality to their failure; the higher they aim, and the lower they fall, the better.

7: Half and Halfs

Comics where failure of one part of the exercise can be forgiven by superlative quality

in another. Peter Milligan’s mini-series Skreemer, for

example, is a case where an excellent script carries the rather rushed artwork of Brett

Ewins and Steve Dillon. Conversely, I doubt if many people have ever bought Moebius’

work on the strength of the scripting.

8: Novelty

Any work which appears to be dramatically original (see “Reader Naivete”) has

the power to excite, and may even begin new styles or fashions in comics. Such work will

occasionally have staying power, but more often either becomes seen in context in the

development of comics (as with the “invention” of chiaroscuro comics by Frank

Miller in Sin City (Note 3), or quickly becomes dated (Simon Bisley).

So, after all this, are there any conclusions to be drawn? Whilst writing this

I’ve managed to quantify my own reactions to the two pieces of work above. With Love and Rockets, for example, the problem could be defined as

reverse “Shared Experience”—in the sense that I find the behaviour of real

people often difficult to interpret, I therefore miss the nuances of the Hernandez

Brothers’ finely drawn characters. Similarly, why like the Silver

Surfer? For me it’s a kind of “Half and Half” as Moebius can do no

wrong (bit of “Nostalgia” there too). As for Stan Lee’s

script—possibly because the first Marvel comics I ever read were reprints of his and

John Buscema’s “Silver Surfer” in TV21, I always

thought of Stan The Man as the Shakespeare of Corn—a writer unafraid to ask the

fundamental questions about the nature of good and evil in the soul of mankind, a writer

unafraid to answer them by staging a fight between a bloke on a surfboard and a three

hundred foot giant in a purple skirt. For me, Stan is right on the fine dividing line

between “Idiosycracy (Good)” and “Idiosyncracy (Bad)”, and the fact

that Marvel chose to publish this surrealist document for just 80p an issue makes it

irresistible.

I hope these criteria may be of use in helping to understand the strange choices that

others make in putting together their collections. Most importantly, I hope that

you’ll write in to Comics Forum with your own opinions on

this subject.

![]()

Notes:

(1) The Panelhouse No 5. - Return to paragraph.

(2) In answer to the “Crimson Tide” question (who did the best Silver Surfer, Jack Kirby or Moebius?)—John Buscema, of course! - Return to paragraph.

(3) I’m not here suggesting that Frank Miller himself ever claimed such a thing, but for a while it was impossible for artists such as Paul Grist to work in their normal style without being accused by some know-nothing of copying Sin City. A similar tale could be told of Dave Gibbons’ use of the 9-panel grid in Watchmen. - Return to paragraph.

|

|

|

|

|

|